So I pat Mrs. Allington on her padded shoulder and say, “There. Don’t you feel better now?”

Mrs. Allington squints at me as if she’s noticing me for the first time.

“Who the hell are you?” she asks.

“Um,” I say. “I’m the assistant building director. Heather Wells. Remember? We met a couple of months ago?”

Mrs. Allington looks confused. “What happened to Justine?”

“Justine found another job,” I explain, which is a lie, since Justine was fired. But the truth is, I don’t know Justine’s side of the story. I mean, maybe she really needed the money. Maybe she has relatives who live in Bosnia or somewhere really cold, and they don’t have any heat, and those ceramic heaters kept them alive all winter. You never know.

Mrs. Allington just squints some more.

“Heather Wells?” She blinks a few more times. “But aren’t you… aren’t you that girl? The one who used to sing in all those malls?”

That’s when I realize that Mrs. Allington has finally recognized me, all right…

… but not as the assistant director of the building she lives in.

Wow. I never suspected Mrs. Allington of being a fan of teen pop. She seems more the Barry Manilow type—much older teen pop.

“I was,” I say to her, kindly, because I still feel sorry for her, on account of the barf, and all. “But I don’t perform anymore.”

“Why?” Mrs. Allington wants to know.

Magda and I exchange glances. Magda seems to be getting her sense of humor back, since there is a distinct upward slant to corners of her lip-linered mouth.

“Um,” I say. “It’s kind of a long story. Basically I lost my recording contract—”

“Because you got fat?” Mrs. Allington asks.

Which is, I have to admit, when I sort of stopped feeling sorry for her.

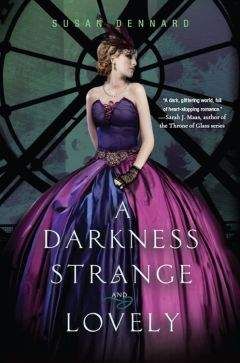

I tell you I can’t

But you don’t seem to care

I tell you I won’t

It’s like I’m not even there

I can’t wait forever

I won’t wait forever

Baby, it is now or never

Tell me you love me

Or baby, set me free

“I Can’t”

Performed by Heather Wells

Written by O’Brien/Henke

From the album Sugar Rush

Cartwright Records

Fortunately I’m spared from having to make any sort of reply to Mrs. Allington’s remark about my weight by the fact that my boss, Rachel Walcott, comes hurrying up to us just then, her patent leather slides clacking on the marble floor of the lobby.

“Heather,” Rachel says, when she sees me. “Thank you so much for coming.” She actually does look sort of relieved that I’m there, which makes me feel good. You know, that I really am needed, if only $23,500-a-year worth.

“Sure,” I say. “I’m so sorry. Was it—I mean, is it—someone we know?”

But Rachel just gives me a warning look—like “Don’t talk about family business in front of strangers,” the strangers being Mrs. Allington and Magda, cafeteria workers not being considered residence hall staff, and wives of presidents of the college DEFINITELY not being considered that way—and turns toward Mrs. Allington.

“Good morning, Mrs. Allington,” Rachel all but shouts, as if to an elderly person, though Mrs. Allington can’t be much more than sixty. “I’m so sorry about all this. Are you all right?”

Mrs. Allington is far from all right, but—even as upset as I am about the fat remark—I don’t want to blurt this out. She’s still, after all, the president’s wife.

Instead all I say is “Mrs. Allington isn’t feeling too well.”

I accompany the statement with a significant glance toward the planter Mrs. A. just heaved into, hoping Rachel will get the message. We haven’t worked together for all that long, Rachel and I. She was hired just a week or two before I was, to replace the director who’d quit right after Justine had been fired—but not out of solidarity with Justine, or anything. The director had quit because her husband had gotten a job as a forest ranger in Oregon.

I know. Forest ranger husband. Hmmm. I’d have quit to follow him, too.

But while Rachel is new to the live-in position of director of Fischer Hall, she’s not new to the field of higher education (which is what they call it when you’re involved in the counseling, but not the teaching, part of college life, or at least so I read in one of Justine’s files). The last dorm—I mean, residence hall—Rachel, a Yale grad, ran had been at Earlcrest College in Richmond, Indiana.

Rachel told me that it had been a bit of a culture shock, coming to New York City from a place like Richmond, where people don’t even have to lock their doors at night. But as far as I can tell, Rachel hasn’t exactly suffered any long-term hardships from her stint in the Hoosier heartland. She has a wardrobe any New York career gal would be happy to call her own, heavy on the Armani and the Manolos, which—considering her salary (not much more than mine, since directors get a free apartment in the building thrown in as part of their pay package)—is quite an accomplishment. Faithful weekly attendance of designer sample sales helps keep Rachel on the cutting edge of fashion. And her strict adherence to the Zone and two-hour daily workouts ensure that she stays a size 2, enabling her to fit into all those models’ castoffs.

Rachel says that if I stop eating so many carbs and spend a half hour on the StairMaster every day, I could easily get back down to a real size 8. And that this shouldn’t be a hardship for me, because you get free membership at the college’s gym as part of your benefits package.

Except that I’ve been to the college gym, and it’s scary. There are all these really skinny girls there, flinging their stick-like arms around in aerobics classes and yoga and stuff. Seriously, one of these days, one of them is going to put someone’s eye out.

Anyway, if I lose enough weight, Rachel says, I’ll definitely get a hot boyfriend, the way she’s planning to, just as soon as she finds a guy in the Village who isn’t gay, has a full set of hair, and makes at least a hundred thousand a year.

But how on earth could anyone ever give up cold sesame noodles? Even for a guy who makes a hundred thousand dollars a year?

Plus, um, as I frequently remind Rachel, size 12 is not fat. It is the size of the average American woman. Hello. And there are plenty of us (size 12s) who have boyfriends, thank you very much.

Not me, necessarily. But plenty of other girls my size, and even larger.

But though Rachel and I have different priorities—she wants a boyfriend; I’d just take a BA, at this point—and can’t seem to agree on what constitutes a meal—her, lettuce, no dressing; me, falafel, extra tahini, with a pita ’n’ hummus starter and maybe an ice cream sandwich for dessert—we get along okay, I guess. I mean, Rachel seems to understand the look I shoot her about Mrs. Allington, anyway.

“Mrs. Allington,” she says. “Let’s get you home, shall we? I’ll take you upstairs. Would that be all right, Mrs. Allington?”

Mrs. Allington nods weakly, her interest in my career change forgotten. Rachel takes the president’s wife by the arm as Pete, who has been hovering nearby, holds back a wave of firemen to make room for her and Mrs. A. on the elevator they’ve turned back on especially for her. I can’t help glancing nervously at the elevator’s interior as the doors open. What if there’s blood? I know they said they’d found her at the bottom of the shaft, but what if part of her was still on the elevator?

But there’s no blood that I can see. The elevator looks the same as ever, imitation mahogany paneling with brass trim, into which hundreds of undergraduates have scratched their initials or various swear words with the edges of their room keys.

As the elevator doors close, I hear Mrs. Allington say, very softly, “The birds.”

“God,” Magda says, as we watch the numbers above the elevator doors light up as the car moves toward the penthouse. “I hope she doesn’t throw up again in there.”

“Seriously,” I agree. That would make the ride up twenty flights pretty much suck.

Magda shakes herself, as though she’s thought of some thing unpleasant—most likely Mrs. A.’s vomit—and looks around. “It’s so quiet,” she says, hugging herself. “It hasn’t been this quiet around here since before all my little movie stars checked in.”

She’s right. For a building that houses so many young people—seven hundred, most still in their teens—the lobby is strangely still just then. No one is grumbling about the length of time it takes the student workers to sort the mail (approximately seven hours. I’d heard that Justine could get them to do it in under two. Sometimes I wonder if maybe Justine had some sort of secret pact with Satan); no one is complaining about the broken change machines down in the game room; no one is Rollerblading on the marble floors; no one is arguing with Pete over the guest sign-in policy.

Not that there isn’t anybody around. The lobby is jumping. Cops, firemen, college officials, campus security guards in their baby blue uniforms, and a smattering of students—all resident assistants—are milling around the mahogany and marble lobby, grim-faced…

… but silent. Absolutely silent.

“Pete,” I say, going up to the guard at the security desk. “Do you know who it was?”

The security guards know everything that goes on in the buildings they work in. They can’t help it. It’s all there, on the monitors in front of them, from the students who smoke in the stairwells, to the deans who pick their noses in the elevators, to the librarians who have sex in the study carrels…

Dishy stuff.

“Of course.” Pete, as usual, is keeping one eye on the lobby and the other on the many television monitors on his desk, each showing a different part of the dorm (I mean, residence hall), from the entranceway to the Allingtons’ penthouse apartment, to the laundry room in the basement.

“Well?” Magda looks anxious. “Who was it?”

Pete, with a cautious glance at the reception desk across the way to make sure the student workers aren’t eavesdropping, says, “Kellogg. Elizabeth. Freshman.”

I feel a spurt of relief. I have never heard of her.

Then I berate myself for feeling that way. She’s still a dead eighteen-year-old, whether she was one of my student workers, or not!

“How did it happen?” I ask.

Pete gives me a sarcastic look. “How do you think?”

“But,” I say. I can’t help it. Something is really confusing me. “Girls don’t do that. Elevator surf, I mean.”

“This one did.” Pete shrugs.

“Why would she do something like that?” Magda wants to know. “Something so stupid? Was she on drugs?”

“How should I know?” Pete seems annoyed by our barrage of questions, but I know it is only because he is as freaked as we are. Which is weird, because you’d think he’s seen it all: He’s been working at the college for twenty years. Like me, he’d taken the job for the benefits: A widower, he has four children who are assured of a great—and free—college education, which is the main reason he’d gone to work for an academic institution after a knee injury got him assigned to permanent desk duty in the NYPD. His oldest, Nancy, wants to be a pediatrician.

![Rick Page - Make Winning a Habit [с таблицами]](https://cdn.my-library.info/books/no-image.jpg)