of the aristocracy (Prussia and Russia), or through a complex combination of these components (the Habsburg monarchy of the XVIII century). But political structures unable to create a «monopoly of legitimate power», such as Rzeczpospolita, became easy targets for rivals who used the signs of the times more effectively.

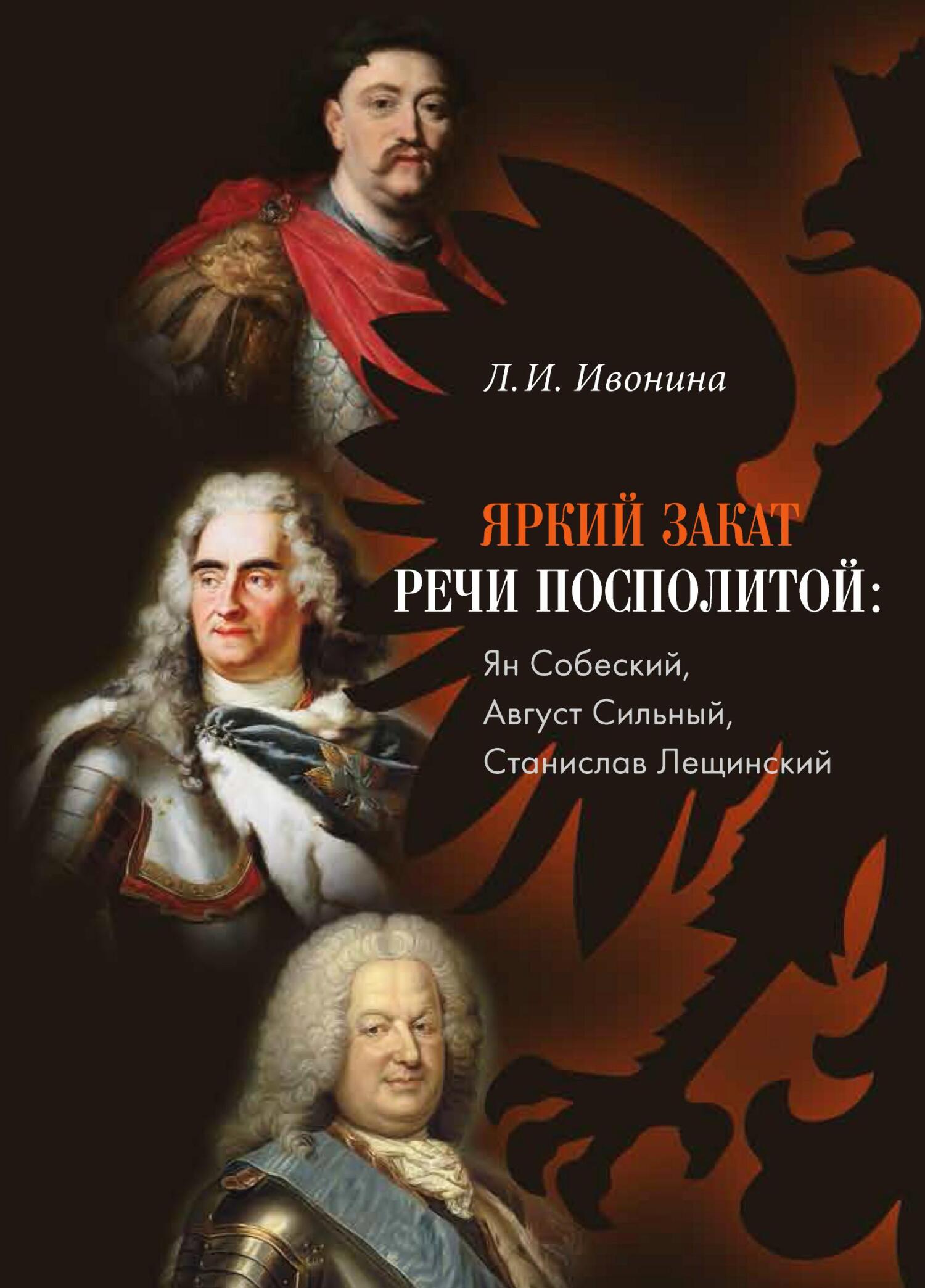

Due to the circumstances, having the necessary talents for successful political, military and cultural activities, Jan III became a key figure of time and place, in order to play an outstanding role in the European events of the second half of the Seventeenth century. He was a man who was sensitive to his time and, focusing on samples of Western European statehood, tried to do everything for his country and, of course, for the creation of his dynasty, everything that was in his power. State and personal interests, politics and love, calculation and recklessness, cunning and trustfulness, education and faith in God were simultaneously coexisted in him. Jan III failed a lot – he did not prevent the decline of Rzeczpospolita, and Europe without him would eventually stand against the Ottomans. The cult of Sobieski resulted not only from his immortal deeds, but developed and exists today mainly thanks to the fact that the ruler was a type of hero both monumental and familiar, with whom the masses of nobility could identify, as well as future generations of his countrymen.

Augustus Strong left his son the excellent cultural center of Europe – Dresden, a mountain of debts and problems with the succession to the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth.The hereditary monarchy dream, which Augustus II cherished in the spirit of his time, was a ghostly illusion; the Polish gentry and the neighboring powers – Russia, Prussia and the Habsburg monarchy opposed to monopolization of power in Rzeczpospolita. At the same time, his many passions and pleasures, many of which resulted in magnificent cultural achievements, were the results not only of personal inclination, but also one of the most successful options for representing the monarchs of his epoch, imitating the French court. They also played a compensatory function against the background of the dififculties that the king faced in real political life. Regardless of the nature of the intrigues of Augustus the Strong, his policy was based on specific domestic and foreign policy circumstances, and its correction would change a little. With a certain degree of exaggeration, it can be said that this ruler, focusing on the French model and having received the Polish crown, was not either a Saxon, or a Pole, or a Frenchman. In fact, he was a type of “citizen of the world”, spreading during the Enlightenment and formed during the globalization processes that had begun.

Stanislas Leszczynski was not a dreamer but a man of action, often lucky in his long life. A man of action, he wanted to return to the Polish throne several times, wanted to make the world happy with eternal peace and ended his life as an active, virtuous philosopher and enlightened ruler. In the history of Lorraine, twice the king of Poland became one of the most famous heroes and was nicknamed Stanislas the Benefactor. Philosopher and enlightened ruler of Lorraine, he turned out to be worthless for the role of the King of Rzeczpospolita largely because of the game “courts and alliances” in the European arena. One of the first among European politicians Stanislas I recognized the future role of Russia in the fate of Poland and in international affairs. Having joined his opponents of Russia by virtue of his political ideas and, as he thought, by will, he, being an exceptionally successful man in life, condemned himself to failure in his striving to rule the country where he was born.

By their personalities, Jan Sobieski, Augustus the Strong and Stanislas Leszczynski actually personified the bright sunset of Rzeczpospolita, unlike its last kings, August III and Stanislas Ponyatovsky, during which reign sun rays did not penetrate through the thunderclouds of the future sections of Poland. Not without success, from time to time each of them sought to change the situation in the Polish-Lithuanian state with its own individual characteristics: Jan III – with mind, military leadership and fierce courage, August II – with passion and representativeness, and King Stanislas – with intelligence and enlightenment.

Собеский под Веной. Худ. Ежи Семигиновский-Элеутер

Ян Собеский, середина 1670-х. Национальный музей, Варшава, авторство приписывалось Ежи Семигиновскому-Элеутеру, затем Даниэлю Шульцу

Портрет Марысеньки Собеской. Худ. Александр Ян Трициус

Ян Собеский и Марысенька в Летнем саду Санкт-Петербурга. URL: https://www.citywalls.ru/house15427.html

Август Сильный. Худ. Шарль Буа

Анна-Констанция Козель с сыном Фридрихом-Августом. Худ. Франсуа де Труа

Петр Первый. Худ. Жан-Марк Натье

Крепость Штольпен. XIX век. Неизвестный художник

Крепость Штольпен. URL: https://www.liveinternet.ru/users/4569551/post266033374/

Аврора фон Кенигсмарк. Неизвестный художник

Мориц Саксонский. Худ. Морис Кантен де ла Тур

Мейсенский фарфор. URL: https://vplate.ru/posuda/osobennosti-mejsenskogo/

Архитектурный комплекс Цвингер в Дрездене. URL: www.ddin.de

Станислав Лещинский. Худ. Жан Жирарде

Мария Лещинская Белль. Худ. Алексис-Симон

Людовик XV. Худ. Шарль Андре ван Лоо

Станислав Август Понятовский. Худ. Марчелло Баччиарелли

Площадь Станислава в Нанси. Фото автора

Вавельский собор в Кракове, апрель 2014 года. Фото автора

Любекское и Магдебургское право – одни из наиболее известных систем городского права, сложившиеся в XIII веке, согласно которым экономическая